Editor's Choice

Don't know where to start? The China, America and the Pacific team at Adam Matthew pick some of their personal highlights from the collection.

The Little Book of Pain and Punishment – Export Watercolours and the China Trade

Susanne Alway

My Editor’s Choice is a small and dog-eared book of export watercolours depicting twelve forms of punishment prevalent in China during the 1800s. It is neatly and simply illustrated, and bound between boards into a little souvenir book for the export market.

My Editor’s Choice is a small and dog-eared book of export watercolours depicting twelve forms of punishment prevalent in China during the 1800s. It is neatly and simply illustrated, and bound between boards into a little souvenir book for the export market.

Such glimpses of Chinese life were mass produced in portside workshops by local artists throughout the 19th Century, and sold to merchants who took them home for curious friends desperate for a peek of the previously unknown oriental world. As the China trade increased, demand for this style of painting also escalated, and export watercolours became a commodity in their own right. Particularly popular were selections depicting the silk, tea or porcelain industries, which complemented and illuminated the merchandise most popular with Western buyers.

Other sets from our selection (the originals are held at the Winterthur Library) depict modes of fashion and furnishing, birds, fish, flowers and insects indigenous to China.

I am always tempted by souvenirs myself, and can see the value in a collection of beautiful pictures in the Chinese style, although this little book of punishments is more  gruesome than attractive. Perhaps these illustrations were intended as a warning for Western merchants as the door to China was pushed further open by clamouring, fortune-hunting foreigners. Although the boon of extraterritoriality largely protected English and American criminals from Chinese laws from the 1840s onwards, such clear depictions of punishment might have made would-be transgressors think before crossing the line.

gruesome than attractive. Perhaps these illustrations were intended as a warning for Western merchants as the door to China was pushed further open by clamouring, fortune-hunting foreigners. Although the boon of extraterritoriality largely protected English and American criminals from Chinese laws from the 1840s onwards, such clear depictions of punishment might have made would-be transgressors think before crossing the line.

Regrettably, we cannot know the crimes that resulted in the punishments shown here, which include flaying, stretching, spanking and the cangue. The paintings tell us a story of pain and punishment, the severity of the torture increasing as we progress through the illustrations. The final page is reserved for the most permanent ‘capital punishment’, and shows a sobbing criminal poised on the threshold of decapitation. The executioner in this final painting looks particularly complacent and cheerful, which is strangely charming and disturbing in equal measure.

For more examples of export watercolours, click here

Houqua – the King of Merchants

Harriet Brunsdon

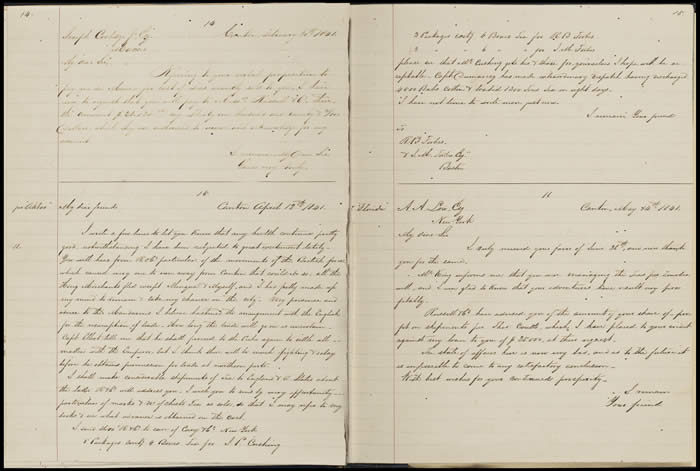

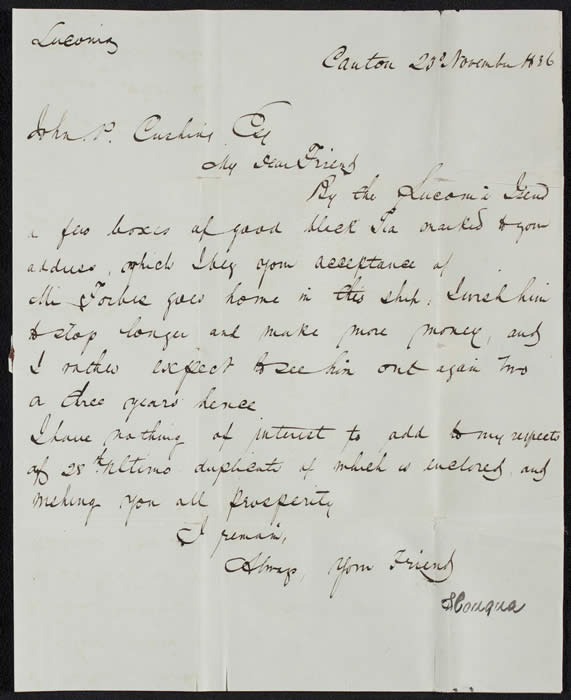

One of the highlights in this project for me is the letterbook of Chinese merchant Houqua, from the Massachusetts Historical Society collection. It contains copies of letters sent by Houqua to Western traders, written out in English by an interpreter clerk.

One of the highlights in this project for me is the letterbook of Chinese merchant Houqua, from the Massachusetts Historical Society collection. It contains copies of letters sent by Houqua to Western traders, written out in English by an interpreter clerk.

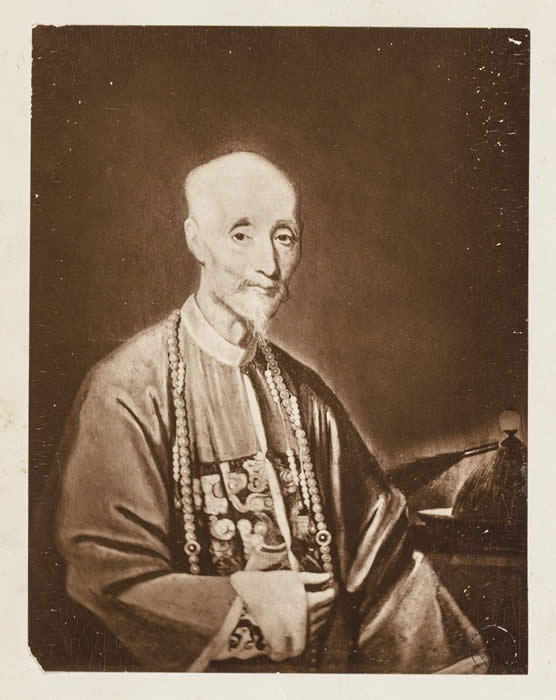

Since first getting involved with this project, I’ve become steadily more and more fascinated by this intriguing figure, who presented such a calm and amiable face to the world while manipulating the Canton System into his own personal money-making machine.

Houqua (1769-1843) was a member of the Canton Hong, the merchant guild that did business with the Thirteen Factories. He was arguably the wealthiest and most famous merchant of them all, and during the mid-nineteenth century he was thought to be one of the richest men in the entire world, having built up a massive fortune through the Canton System. As one of the few Chinese merchants authorised to trade with Westerners, Houqua enjoyed a comparative monopoly over the sale of tea, silk and porcelain, with only his fellow Hong merchants for competition.

His success is chiefly down to a knife-sharp intelligence and a ruthless attitude to business. He frequently undercut his competitors and played the system, cleverly manipulating the rules and politics to get the best deal.

But he also built up strong relationships with the American and European traders in the Factories, and this is what comes across so strongly in his letterbook. Houqua is politeness itself, treating each and every Westerner with whom he did business with the utmost courtesy and respect. He meets them as equals – an astonishing feat in nineteenth century China, where all foreigners were mistrusted to the extent that they were not permitted direct contact with the world outside their Factories. But to Houqua, all men of business the world over speak the same language and understand the same culture – money.

We are left with an impression that a great affection exists between Houqua and his recipients – among whom are American merchants John Perkins Cushing and Robert Bennet Forbes – and that they all regard each other as honoured colleagues and good friends. It is evident that the Western traders are not only grateful for Houqua’s advice and assistance, but they also enjoy his company and correspondence. Further letters from Houqua to the American merchants can be found in the Boston Athenaeum collection.

We are left with an impression that a great affection exists between Houqua and his recipients – among whom are American merchants John Perkins Cushing and Robert Bennet Forbes – and that they all regard each other as honoured colleagues and good friends. It is evident that the Western traders are not only grateful for Houqua’s advice and assistance, but they also enjoy his company and correspondence. Further letters from Houqua to the American merchants can be found in the Boston Athenaeum collection.

We can learn an astonishing amount about Houqua from his letters. For instance, rather surprisingly, he invested some of his immense fortune in the United States, and asked his American colleagues for advice. For a Chinese man in this period, however wealthy, to turn his attention to a foreign nation in this way seems very radical, and goes to show what a lynch-pin Houqua became in the relationship between the China and the West. On the one hand he represented the Canton System of traditional, hard-nosed capitalism, and on the other he helped pave the way for communication with the West based on mutual respect and trust.

I could go on and on, for there are many stories that remain to be discovered about this mysterious hero of commerce. I hope you enjoy exploring this wonderful source as much as I have.

Bêche de Mer, Shark Fins and Gold; a selection of commodities packed for the China Trade

Sarah Hodgson

During the eighteenth century American merchants sought to establish trade with China. Their ships set sail from New York, Boston, Salem and Philadelphia laden with tea, ginseng and opium; all profitable and powerful commodities that could be traded with the accomplished merchants waiting at Canton. However competition from establishments such as the East India Company kept the American merchants busy; they had to find products which satisfied the niche and sometimes peculiar tastes of the merchants at Canton.

During the eighteenth century American merchants sought to establish trade with China. Their ships set sail from New York, Boston, Salem and Philadelphia laden with tea, ginseng and opium; all profitable and powerful commodities that could be traded with the accomplished merchants waiting at Canton. However competition from establishments such as the East India Company kept the American merchants busy; they had to find products which satisfied the niche and sometimes peculiar tastes of the merchants at Canton.

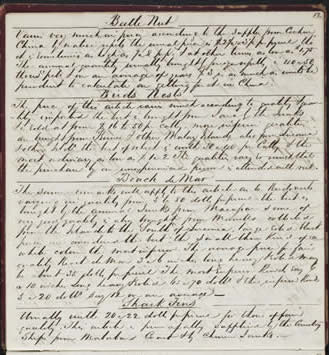

Whilst indexing the Forbes Papers from a collection at the Massachusetts Historical Society I came across a business record item which details specific goods that were to be packed for the China trade between 1828-1829. The record contains a fascinating list of products including the following: bêche de mer, shark fins, tortoise shells, pearl shells, opium and gold amongst others. Trading goods such as shark fins is quite horrifying today, but this document is rich in its explanation of the quality of such products and the price they fetched.

One product included is bêche de mer, pictured in the above image. Found in the Pacific Islands, bêche de mer is a Chinese delicacy which was added to soup. Translated, bêche de mer means sea slug! Traders collected the niche commodity, often found in birds’ nests, or relied on the experience of the natives to collect the product for them for a small fee. Such specialized products were never going to put the East India Company out of business or create fame and fortune for the merchants who traded them. They do however offer a fascinating glance into the demands of the market at the time.

Captain Limeburner’s Race to China

Ben Lacey

One of the tasks I was set during this project was to collect data for the mapping of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century voyages. This gave me the opportunity to read through some of the ship logs and journals that form part of the document collection. Many of them offer a fascinating insight into life, attitudes and emotions aboard their ships, as the authors recorded far more than just the location and course of their vessel.

One of the tasks I was set during this project was to collect data for the mapping of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century voyages. This gave me the opportunity to read through some of the ship logs and journals that form part of the document collection. Many of them offer a fascinating insight into life, attitudes and emotions aboard their ships, as the authors recorded far more than just the location and course of their vessel.

Take, for example, Henry Blaney’s journal of the voyage of the Samuel Russell, a printed copy of which forms part of the collection from the University of California, San Diego. This account records the journey from New York to Canton made by a clipper ship whose captain was especially motivated when it came to reaching his destination. While still in New York Captain Limeburner was described by Blaney as ‘anxious to get off’, and when they reached Anjer in Indonesia the reason for this became clear. It transpired that Captain Limeburner had made a bet with the captain of another clipper, the Ariel, concerning who would be the first to make it to China. The prize was to be eighteen fat ducks, paid for by the loser. The Ariel had set off first, but was found to have not made Anjer by the time the Samuel Russell anchored there. Limeburner therefore collected the ducks and left an order for his rival to pay, and a note saying ‘“if he caught up with us he might have them”’.

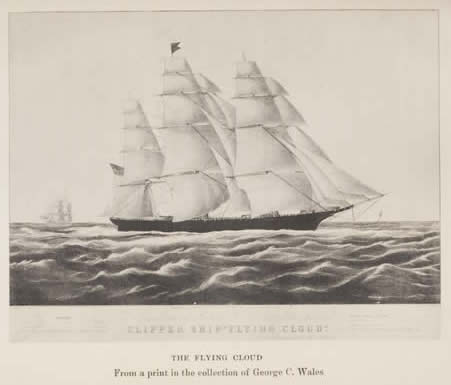

In the mid-nineteenth century this friendly rivalry between clippers and their captains was a common feature of the China trade. Back in the home ports it could turn into more than just a matter of ducks and pride, with large sums of money sometimes wagered on the voyages. In Britain, this culminated in ‘The Great Tea Race of 1866’, a competition to see which of nine ships would be the first to reach London with the new season’s tea. Meanwhile, in the USA, records for the fastest port-to-port voyages were hotly contested. Blaney mentioned his own admiration for the Flying Cloud, a ship famous for holding a record of 89 days for the journey from New York to San Francisco.

This competitiveness is just one aspect of the human side of global trade in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Plenty more information about life at sea emerges from the logs and journals. One can find tales covering everything from the love life of a sailor, to attempts to blow up a ship, and even the ongoing battles between a ship’s cook and the vessel’s recalcitrant pet monkey. Each offers a different angle on the lives and feelings of the officers, crews and passengers who participated in the China trade.

Nauticon: A Woman at Sea

Paul Middleton

![]() It took me around twenty pages of reading Islands Seen by Ship Nauticon before I realised that this was not just another logbook. I think part of me could not comprehend that this document existed. That a woman was not only allowed on board a whaling vessel, but that she had produced such an articulate and detailed account of her remarkable journey in the process. There are many different logbooks within our resource, however Susan Veeder’s story from the Nantucket Historical Association is, in my opinion, by far the most astonishing, and a definite highlight of the collection.

It took me around twenty pages of reading Islands Seen by Ship Nauticon before I realised that this was not just another logbook. I think part of me could not comprehend that this document existed. That a woman was not only allowed on board a whaling vessel, but that she had produced such an articulate and detailed account of her remarkable journey in the process. There are many different logbooks within our resource, however Susan Veeder’s story from the Nantucket Historical Association is, in my opinion, by far the most astonishing, and a definite highlight of the collection.

In September 1848 Susan Veeder, her husband Captain Charles Veeder, and their sons set sail from Nantucket, Massachusetts, beginning a four-and-a-half-year-voyage that would span three oceans and over fifteen different ports, all in the search of whale oil. Her incredible watercolours are scattered among detailed descriptions of whale hunts that really capture the drama of each chase, however it is her unique tales of life on board that really set this logbook apart. ![]()

The entire journey was a rollercoaster of emotions for the couple, due in part to the birth, and subsequent death, of their daughter Mary Frances. Pregnant when boarding the Nauticon, Susan Veeder was left in Talcahuano, Chile, whilst her husband continued the hunt in the Pacific. There, on 29 January 1849, she gave birth to a baby girl and mother and child later returned to the ship to join the rest of the family. Veeder included occasional updates on the baby within her logbook, for instance noting how: ‘Mary Frances is 11 months old, has 7 teeth. Creeps all about the ship and is very cunning. She is now on deck taking a ride in his wagon.’ Tragedy struck, however, on 5 March 1850 when Mary Frances succumbed to illness and sadly passed away. Veeder was understandably distraught, and had her doubts as to whether Mary Frances’ death was due to illness, or as a result of an overdose of prescribed medicines by a doctor at the port of Tahiti. The child’s death was never mentioned again in the logbook. Instead, Veeder continued to describe the many whale hunts that followed as the ship entered the Arctic Ocean, as well as including even more remarkable tales of life and death at sea.

Veeder’s account on board the Nauticon is truly incredible. The logbook has enough drama and heartbreak to rival any work of fiction, which makes it one of the most readable items within the collection. The log is much more than a simple narrative of whaling; it is a window into Veeder’s own voyage of discovery, an extraordinary tale of a woman at sea.